You are in the supermarket and you buy a huge cream cake. You are also on a diet.

Does this mean you intend to break your dieting?

There are times when the things we want to observe and measure are difficult to get a precise angle on. They might be hidden or there may be no standardised way of measuring them. It is at these times we can use a proxy measure.

What is a proxy?

A proxy is something you use to stand in for the thing you cannot measure.

You may have heard of a proxy voter - someone who stands in for a voter who cannot cast their vote in person.

In research, a proxy is something that is related to (e.g. something that you would do/use/create at the same time as the thing you are measuring) or is similar in characteristic to the thing you really want to measure.

Take for example altitude. How do you measure how high above sea level you are? This is information vital to airline pilots and mountaineers. Experiments from the 1700s demonstrated that air pressure reduces with altitude and is a useful proxy. So barometers were proxies that were used as the first altimeters.

Cakes & Diets

Using proxies is fine when we know there is a reasonable relationship between the two measures. But let’s take a different example: How do we measure people’s intentions and feelings.

We have limited ways of accurately measuring an intention, even fewer of expressing them in a way that can be understood.

Many of us carry one if not a multitude of supermarket loyalty cards and use them regularly when we shop. These cards not only give us rewards but provide the supermarkets with insights into us as individual shoppers.

So what if they were to use the data they had to measure the intentions of shoppers to go on diets in January? Does the presence of cakes in a shoppers basket really mean they aren’t or won’t be sticking to their diet? It is not beyond the realms of fantasy as Tim Hartford demonstrates in his book "How to Make the World Add Up"1.

Maps and mobility

This might seem a trivial example so let’s use one that is more recent and impactful in our everyday lives.

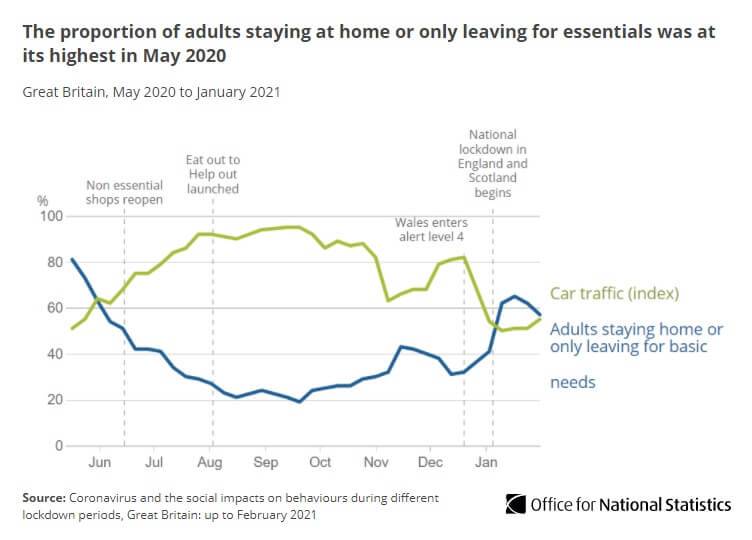

As much of the UK entered a lockdown in January 2021 the stakes were somewhat higher than a diet. To avoid the collapse of health services under a newer strain of Covid-19 Governments needed the public to adhere to stricter rules and the message was once again to “Stay at Home”.

Early commentary of the lockdowns suggested that the public were adhering less to this lockdown than the first national lockdown in March 2020.

New data from TomTom has revealed a significant drop in the number of people driving on the UK's roads during lockdown https://t.co/HfvrO7Xbq5

— Sky News (@SkyNews) April 21, 2020

When is a journey not a journey?

They looked at various sources of mobility data from travel planning searches (e.g. Citymapper data) to journeys taken (via Google and Apple). All of these pointed towards more movement in January than the lockdown in the previous March.

But there is a problem in using such data to draw these conclusions. Not all “mobility” data provides conclusive proof a journey was taken. And actual travel undertaken may have been for legitimate reasons and not frivolous rule breaking.

The definition of what is and isn’t rule breaking isn’t clear from the data alone.

A direction search might be based on curiosity (guilty hand being raised by the author - there are enough of us geography/map nerds out there who do this for fun!).

A journey might be taken for legitimate reasons like work and not to break or push the rules.

Whilst the data can show varying degrees of certainty over mobility patterns, there is a danger of reading into it intentional boundary pushing and rule breaking. The measures used simply do not allow us to infer such a result.

Hints need confirmation

This is not to say proxy measures are unhelpful. Choosing proxy measures that offer greater accuracy and direct relevance are critical.

But in lieu of large scale qualitative surveys, mobility data in the case of Covid rule breaking allows us to look into what might be happening. And it is a big might.

Wider surveys later confirmed behaviour did change. But the correlation between mobility and adherence to the rules should not automatically be assumed to prove causation.

To understand the data we always need to place it into a wider context - in this case what the rules allow people to move around for and importantly how those rules were communicated and interpreted. We can use it to identify questions that will help investigate through other means but it does not infer a conclusion on its own.

In a curious way I don't think the referendum was about Europe. Of course it technically was but what were people really voting about and I think if you ask that question they were voting for change and if you're going to argue for change, important thing is to dangle in front of people something that they can identify that they want to change.

Of course, this is not an isolated instance of proxy measures being used in everyday life. From the underlying motivations of voters in the Brexit referendum to what expressed religious beliefs in the census say about Britishness, one measure stands in for another in making sense of the world.

This claim is particularly lolz.

— John Burn-Murdoch (@jburnmurdoch) December 5, 2022

The decline in Christianity in the UK has been driven overwhelmingly by *white Britons*, less than half of whom now say they are Christian, down from 69 per cent in 2011, a loss of about 7mn 📉 pic.twitter.com/plDTT1f0Ol

Proxy measures can be helpful only if we recognise their limitations. To understand the things that the proxy suggests is happening it is always essential to ask further questions about why and where possible get closer to the real measures however hard they are initially to find.

You can’t have your cake and eat it but buying a cake doesn’t mean you are going to eat it yourself.

I love how Dr Rob ways gets to the heart of what is real, but he most go through life sooo frustrated at this stuff. https://t.co/LPZqsMXRBA

— bruce whitear (@WhitearBruce) November 29, 2022

1 Harford recounts the story of a US retailer who used items bought by a customer as proxies for their pregnancy. Read the full story on pages 167-175 and see how proxies are essential in our everyday life where big data and algorithms are involved.

2 Michael Heseltine was interviewed in the Leading podcast by Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart (episode available from Apple, Google and Spotify - 6m 45s for the clip)

You may also be interested in

Thought, inspiration and how-to straight in your inbox - Sign up today

By subscribing you will receive our newsletter up to 4 times a year and occasional news of forthcoming events. You can unsubscribe at anytime.